Like for many people probably, it was Patrick Blanc with his artistically planted green walls who first captured my attention and imagination years ago. What a vision: a city where instead of staring at grey concrete and dirty bricks the walls were covered in lush greenery! I remember breaking my budget when his book "The Vertical Garden. From Nature to the City" was first published... Hence I really had looked forward to his introductory talk - the sprinkling of "stardust" to the conference - and he didn't disappoint. Lively and engaging he took everyone on a journey from his first attempts at creating green panels in his home about 30 years ago to the high-profile and highly prestigious projects of latter years.

Being a plant scientist first, he spoke about how he searches around the world for plants (or plant communities) that are naturally adapted to growing on near-vertical surfaces: from boulders and waterfalls in the tropical rainforests to cliff faces in karst mountains. These natural candidates he then aims to harness for use in his Mur Végétals. Visual appeal (different textures and shapes, for instance) being as - or almost as - important as adaption to the situation. Lately, he seems to increasingly look for plants native to a project's location: in an example from Japan he pointed out how he had collected plants from mountains and forests just 15 - 20 km away, had a local nursery propagate them to provide the numbers required and then included them in the green wall, adding educating panels for people to relate to it all the better.

What distinguishes his walls from many other offerings that exist today, I think, is that they are also a form of art - almost like a painting. The drifts of plants flow into each other seamlessly whilst with more conventional green walls you'll get what I'd call a "pixelated effect", the grid of modules clearly visible. Which, of course, makes maintenance easier since you can easily exchange plants that have died or suffered for new ones.

I have heard people say that Blanc's are - in terms of the benefits usually expected of green walls - among the least efficient. This may well be, but as a means of raising awareness, capturing the public imagination - in short: in terms of marketing and public relations and making the case for greening facades - they are hard to surpass. I witnessed a lady working for a large store with an indoor green wall by Blanc who was there to meet participants of the WGIC on a field trip to green infrastructure examples around Berlin: she positively eulogised about Blanc's work. It seemed genuine, all the more so for being expressed privately in talk with some visitors rather than in an official capacity.

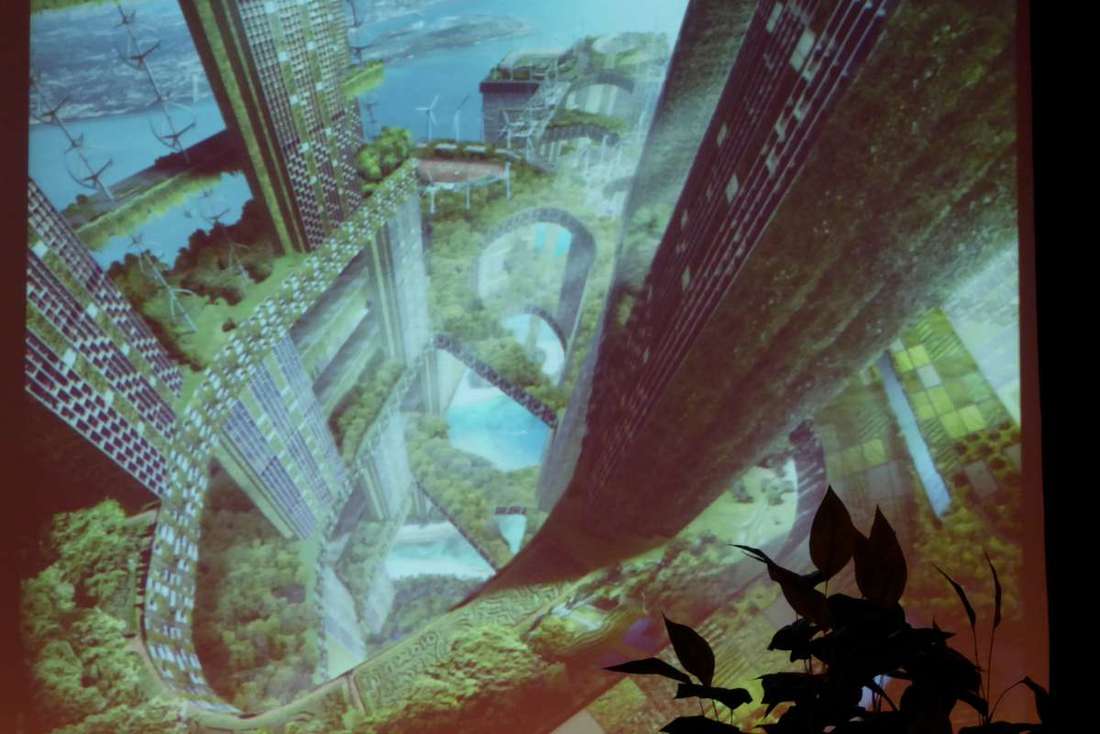

Topics covered ranged far and wide: from urban rainwater management to research into the improvements to room-climate plants can make – and how to keep the latter happy, too. From a survey of the vegetation on green roofs 20 – 30 years after they had been installed to talks on zero-acreage farming (the latter is the term used for urban food production which does not take up a separate “foot print” on the ground because it uses roofs, facades or rooms in existing buildings). From the legal framework and financial incentives available to build green infrastructure to IT tools designed to help architects, landscape designers, developers and those responsible in local authorities to do just that and work towards greener cities. And of course there were many real-life and best practice examples as well as bold visions for the future.

The most impressive bit of all is that much of this green infrastructure isn’t just plans on a drawing board - but exists for real already. It definitely wasn’t just my jaw which dropped! There was an audible murmur and sighing amongst the audience, the general consensus seeming to be that many wished they would be given the chance to create projects like these just once in their life… And that we had a lot of catching up to do in these parts of the world!

In fairness though: the climate in Singapore is so conductive to plant growth you could probably plant a broom stick and it would sprout leafs – a definite advantage compared to our European cities where you often have to content with (and find suitable plants for) freezing conditions in winter and hot periods of draught in summer. Still: as a vision of what can be done if the political will and commitment is there, these talks certainly were an inspiration.

Nearer to home there were case studies from Berlin and other German and European cities, such as Vienna, Paris, Porto and Amsterdam. For London, Dusty Gedge - who also is President of conference co-organisers EFB - gave a ten-year review of “Delivering Biodiversity and Green Infrastructure” in my adopted city, and Pete Massini spoke about “Greening a green city – the London experience”. Personally, I’ve always considered Berlin to be a much greener city than London, but I suspect statistics aren’t on my side: it’s just that trees in streets are much more visible than the many private gardens and squares tucked behind houses and walls.

And if you look at it more selfishly: urban green improves air quality and reduces a city’s heat island effect when temperatures are rising – something we all benefit from. It also can play a role in reducing energy consumption and using energy more efficiently. For example, one speaker mentioned findings that the air-conditioning system of a building with a green roof needs 20 - 50 % less energy than one without a green roof – quite simply because the green infrastructure will have cooled the air down a bit already before it enters the air-conditioning system.

With climate change and its accompanying challenges for the environment as well as the economy, green infrastructure will be increasingly instrumental – even decisive - to help us cope. Those were, of course, prominent themes. But a very large number of talks also looked at the non-quantifiable benefits of getting more plants (and with them nature) into cities. In addition to the above mentioned effects on human well-being, increasingly the focus - not just of research - is on social cohesion, too. About creating places to get together, learn and interact, such as community gardens or social enterprises.

Another talk I particularly liked was one on biophilic design: The speaker argued that evolution had hardwired us to like certain natural features - such as water or a sheltered spot with a good view or vantage point - which were of advantage to our ancestor's survival and that hence we consider these to represent beauty. Apparently, the term was first used in 1973 by Erich Fromm with many publications into the subject following since. Referencing from some of these, he pointed out that there is a clear business case for biophilic design which means designing environments based on human evolutionary preferences.

To take just the example of the work place: productive, healthy people are good for business. With the mantra "where we feel well, we perform well", productivity is the watchword here. Especially, he said, since productivity costs are 87 times greater than energy costs in the workplace. In one example there was apparently a 299% return on investment. There are, the speaker claimed (and it sounds logical enough), huge potential financial savings to be had across many sectors of society. It is actually possible to scientifically measure the physiological impact of design (i.e. the health benefits or lack thereof) - such as for instance on blood pressure. He thus urged architects, landscape designers and of course developers to turn to and apply biophilic design - and not just in commercial developments.

Finally, on the practical side of things (and without having expert knowledge to boost this claim), technology developed by European project Green4cities is likely to prove particularly useful and relevant in the near future. It is billed as a planning and certification tool for green infrastructure that can be fully integrated in the urban planning and development process. Detailed simulations of microclimates (of e.g. an urban area in its present state as well as with planned changes implemented), of water retention, wind fields and the storing of CO2 are just part of it. There is also a "toolbox" for urban development and planning which starts with an assessment of the current situation and its problems leading to a simulation of more general or large-scale urban designs and/ or allows the detailed planning for individual quarters.

For those interested, here is a list of talks and speakers at the WGIC 2017, with many presentations for downloading as a PDF.

As for myself – I’ve only become more fascinated and curious about the whole subject area. So expect to hear more of that in the future of this blog!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed