Margaret Mee, for those who have not come across her name before, was an Englishwoman who – in 1952, at the age of forty-three – moved to Brazil and only there found her true calling as a botanical artist. Fascinated by the flora of her adopted country, over the next thirty years she went on fifteen expeditions into Amazonia. These were self-arranged, and often she was accompanied by no-one but native Indian guides.

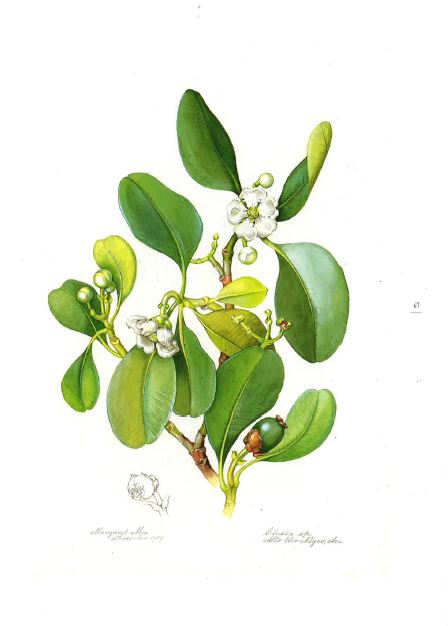

There in the wilderness Mee would search for and collect plants and sketch them at great detail in situ. If possible, she'd then bring them back to Rio, to be grown on in her own garden or that of her close friend, the famous landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx. Back home, she'd also compose and work on her paintings from the many field sketches she had made. These paintings instantly met with great acclaim from botanists and lovers of botanical art.

However, Margaret Mee is famed not only for her outstanding art but because she became one of the first people to draw attention to the wholesale destruction of the Amazonian rainforest. Extremely concerned by what she saw, she publicly and very outspokenly campaigned for it to stop. This earned her so much affection and respect that apparently she had a samba school named after her in the Rio Carnival, with three thousand eco-friendly dancers parading to a Margaret Mee theme song – the ultimate honour in Brazil!

This celebration of a remarkable woman probably happened after she died in 1988. I myself have been enthralled by her work and life since I first came across it in 2004 via the book Margaret Mee's Amazon. Diaries of an Artist Explorer. It beggars belief what this by all accounts petit, shy and almost frail woman took in her stride: not just the physical hardships of journeys at the most basic levels of comfort, but malaria, hepatitis, tropical fevers and several near-drownings. Oh, and a direct threat to her life by drunk, belligerent gold prospectors! Luckily, she’d also carry a small revolver amongst her brushes and paint pots…

All the more tragic then, that she would eventually be killed in a car accident on a British motorway! It is tempting to conclude that British roads are more dangerous than the Amazon jungle… But back to the exhibition at Kew. I had not come across her original paintings before, only reproductions in books. They are – quite simply – magnificent.

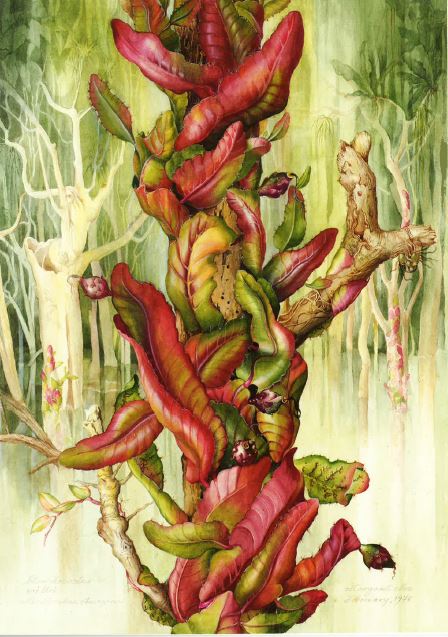

What I found particularly touching, however, are the little marks left by her pencil: painted over, sometimes apparently erased but not quite, they talk of changes she made on the go - from her first lay-in to the finished painting. You only see them at close quarters and you won’t notice them in quite the same way in any printed reproduction. For instance, in her picture of Urospatha sagittifolia (see below) Mee changed the picture from including an inflorescence on the far right to only its stalk, realizing that the overall composition would gain. So she erased the top bit – you can see this in the original.

To me, those “blemishes” are what make these paintings “human” and approachable. In most reproductions they are so immaculate, it’s hard to believe a real human being, some actual person created them. Which, by the way, I find true for most of botanical art: it’s so perfect, so blemish free, every last mark and smudge carefully removed, I find it sterile in a very strange way, hard to grasp this art is “hand-made”. But here you can see someone painted these amazing pictures by hand! And it makes you realize all the more the whole scope of Mee’s artistic ability.

Also, her colours have a vibrancy, depth and saturation that I find lacking in the work of many other botanical artists. All too often, colours in botanical paintings are pale, translucent, almost anaemic and without any sparkle – a ghost of a plant. Mee’s colours sing with joy and life. But that may be to do with her having worked in gouache rather than the more common water colours.

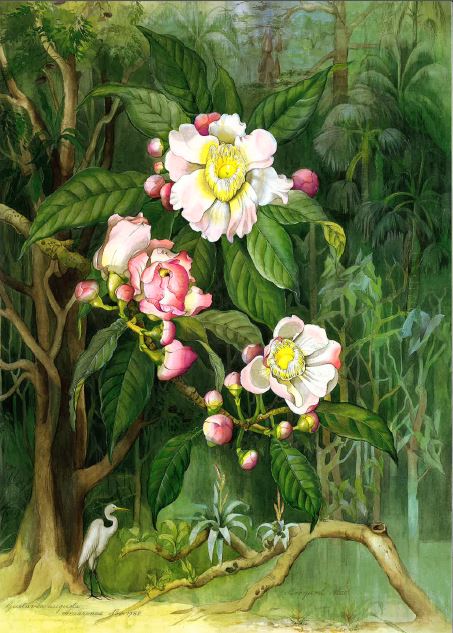

I was intrigued and inwardly smiling to discover that her first painting in the Amazon was of a Cannonball tree (Couroupita guianensis). This plant – or rather its flowers and unusual fruit which give it its common name – stole my heart on my first ever taste of the tropics in Singapore so many years ago. The unusual, fleshy blooms are pollinated by bats, though insects will also visit. It is one of those species which you can only meet in the tropics: a huge cauliflorous tree, i.e. flowering from its trunk, you can’t grow it properly in our climes, not even with the help of a greenhouse or conservatory.

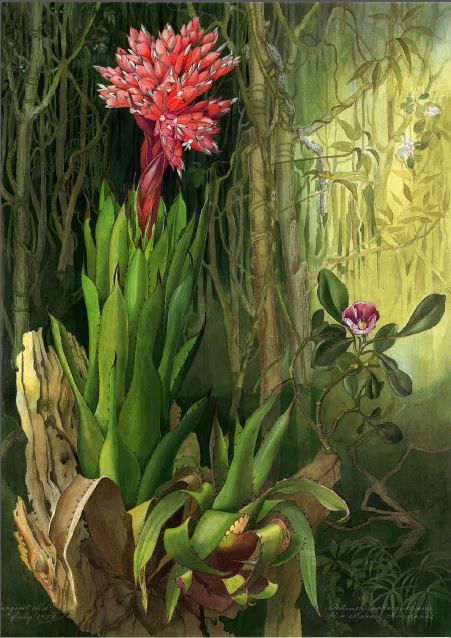

But the paintings Margaret Mee perhaps is most famous for are also the ones I love best by far. Increasingly concerned by the destruction of the rainforest she witnessed, she wanted to show people in her paintings that plants do not exist in isolation. That there is a whole ecosystem behind which we cannot afford to lose but should cherish and protect. So to raise this awareness, she strayed from the traditional path of botanical art which demands a plain white background to aid scientific identification of a plant.

Instead, in some pictures she would paint a particular species in the foreground, detailed as usual, but include a whole rainforest setting as the backdrop. Thus, she dramatically altered the paintings’ mood. You no longer see just an orchid, or a bromeliad or a flowering branch – you are transported into the green gloom and eternal twilight of the jungle, a magic world, realm of fables and fairy tales or the green hell of the tropics, depending on your disposition. It was the cover picture of a Gustavia (see below) which drew me to her Diaries in the first place.

I love forests and woods of any kind, they are my favourites – whether European woodland or temperate or tropical rainforest. And years ago, before we had children, my man and I spent a little time travelling Ecuador. There, we also went to the Cuyabeno Wildlife Reserve, near the border with Colombia. Whilst not on the banks of the Amazon itself, it is part of Amazonia. I remember the flooded rainforest, trees half submerged or growing out of the water, laden with bromeliads, orchids and other epiphytes. Swampy tracks. Access to many parts only by boat. So Mee’s pictures resonate on that front, too: they bring back precious memories.

(Speaking of Ecuador, I loved the cloud forest even better! I took so many slide photographs... Maybe I’ll write a post about Ecuador one day, but currently I do not have the equipment to digitalize those slides.)

Anyway. Even though I have dwelled on Margaret Mee for so long, hers are not the only botanical paintings currently on show at the Shirely Sherwood Gallery of Botanical Art in Kew! There are those of early explorers to Brazil and those of established contemporary Brazilian botanical artists, most of them inspired by Mee, sometimes hung in direct comparison with her paintings of the same plant. And finally there are those of scholarship students on the Margaret Mee Fellowship Programme: in her honour, one Brazilian botanical artist per year gets a grant to spent five months at Kew to be tutored by Kew’s own resident botanical artists.

The exhibition is on until the 29th of August. While perhaps not such a blockbuster as the Royal Academy's Monet to Matisse show, it sure is more than worth a visit.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed