Once there though, you can travel if not the world then at least gardens of various international destinations. A great advantage of this is being able to compare the differences between traditional Korean, Chinese and Japanese gardens, for instance - both in style and atmosphere. Of course, there is no one "Chinese" or "Japanese" style. But there are certain elements which tend to define these gardens and make them distinct. And here, without much knowledge into the specifics, you can soak it up and get a feeling for these differences. For the gardens here in Berlin-Marzahn are not a European make-believe version with some acers, stone lanterns and buddhas randomly dotted about - they are as real as they could possibly be outside of Asia, many not only having been designed by artists from the respective country but using original materials and even crafts people from there to build them.

I've seen a real Japanese garden before at Holland Park, London, which I also love (I'm not sure the Japanese garden at Kew qualifies to the same degree). This one here is more intimate, however. And an equally intricate and sophisticated true Chinese garden was one of my favourite discoveries in Frankfurt am Main, Germany years ago. But a Korean garden was entirely new to me. The lasting impression of the latter would be lots of walls, yards and fairly few plants. But maybe I was just not taking enough time.

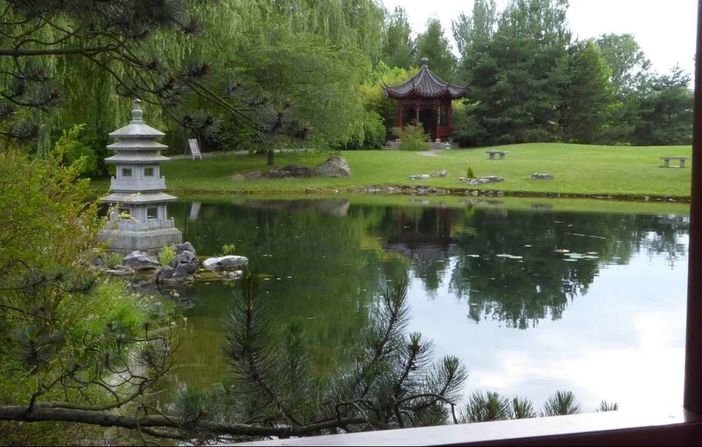

This garden was the first to be opened on site, in 2000, and at its centre there is a 4500 sqm sized lake and various buildings and zigzag bridges. I love the Asian way with naming things - it is always so poetic and evocative. So here we have the tea house called "Mountain House of the Osmanthus Juice" (I hope my translations are correct!), the entrance hall "Parlour of the Fair Weather", the "Pavilion of the Quiet Moonshine" and a stone "boat" called "View to the Moon" among others.

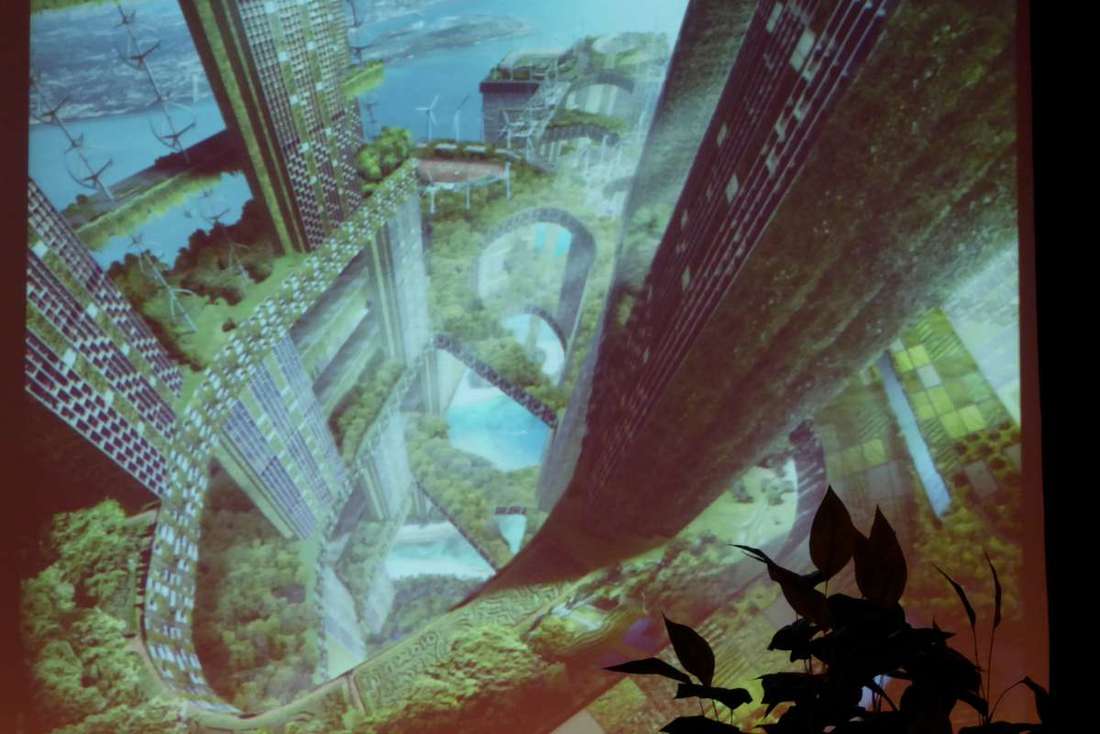

But maybe I'm wrong to expect a "garden" in our temperate climate sense of the word. An explanation states that the gardens express an important aspect of Balinese philosophy, namely the endeavour to reach a state of harmony between man, his surroundings and the whole universe. It also explains that the village buts on to jungle, as is common in the south of Bali. Indeed, it explicitly stated that "in Bali, there are no gardens in the common sense since plants are not chosen by artistic criteria but purely according to their use - as medicinal plants, food or for ornamental reasons." So there you are.

Karl Foerster, of course, was one of, if not the most famous and influential German gardening personalities of the 20th century, celebrated as a garden writer and creator, garden philosopher, nursery man and, most lastingly perhaps, plant breeder who introduced many a fine selection of grasses and perennials, especially as astilbes, delphiniums and asters. His style owes to William Robinson, I'd say, and he is especially known for his famous sunken gardens and quotes like "A garden without phlox is an error."

I do not include any pictures of the Foerster garden here; firstly because I do not think it to fit well here and also because I don't have any: by the time I'd arrived there it was not only late in the day but my camera's battery dead after a day working overtime... If that isn't inducement to come to IGA 2017, I don't know what is ;-). More about the latter in my next post.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed